Antique dealers may respond hopefully to dusty bits in attics, but true cooks palpitate over more curious odds and ends: mushroom stems and tomato skins, poultry carcasses, celery leaves, fish heads, and knucklebones.

—The Joy of Cooking

***********************

I clip the leash on the dog and we march out into a balmy January day. Over the river, the sun is rising, a beautiful band of liquid gold poured gently onto the horizon. It is almost sixty degrees out, and my jacket swings, jauntily unzipped, as Greta and I head out for a long sniffing walk. We wander past Sandy’s house; we meander up the drive by the Helen Purcell Home. The snow has melted, and the old dog, blissfully energized, chortles up wonderful scents.

But there’s an undercurrent to the breeze, and clouds begin to gather as we wander, and by the time we are back in the driveway, drops are falling. It will rain all day, the weather app tells me, and, along about four o’clock or so, the rain will turn to snow, and the streets will freeze, and travel will not be a smart or easy thing.

I think that it’s a day to make broth, and, after tending to the little dog’s need for treats, I turn the oven on to warm. I hunker down, refrigerator door open, searching.

I pull out the carcass from the turkey we roasted this week. In the crisper, half an onion waits in a baggie, nestled next to celery and carrots and the end of a bag of salad. I pull all these out, swivel them up to the corner and turn back to search through shelves.

I uncover a little container with a scant serving of green beans. I find a little bit of broccoli, and, behind the milk and the plastic jug of orange juice, I discover the end of a bag of spinach.

I gather these things and stand up, stretching, and I lay everything on the counter and survey.

Then I pull the old black roasting pan, its bottom raised and indented to form its own built-in roasting rack, from the top of the cupboard. I rinse and dry it, and then I begin.

First, of course, the turkey bones, which I crush slightly. I cut up the onion, and three celery stalks and two fat carrots, and I put them, too, into the pan. I scrape the leftover veggies into the mix and consider. Then I cut up another small onion and add it to the mess, and I throw in three peeled garlic bulbs. I drizzle it all with olive oil and sprinkle on a generous helping of dried herbs—herbs that Terri sent me, herbs that were grown and harvested and dried and blended on the farm of her dear friend. I believe, I really do, that all that care and attention comes out in a delicate, decided flavor.

I throw in a bay leaf, a teaspoon of pepper, enough coarse salt to make a one-inch pile in the palm of my hand. I toss it all together, and I slide the pan into the warming oven.

Rain, now, is lashing the windows. The scent of the roasting veggies and bones begins to rise almost immediately.

Jim stomps down the stairs, still sleep-stippled. “What’s cooking?” he asks. After I tell him what’s in the oven, he says, “It smells GOOD. People should bake that up when they’re trying to sell their house.”

He’s right; the roasting bones and veggies smell like warm and homely comfort. I wait fifteen minutes before I pull them out and stir.

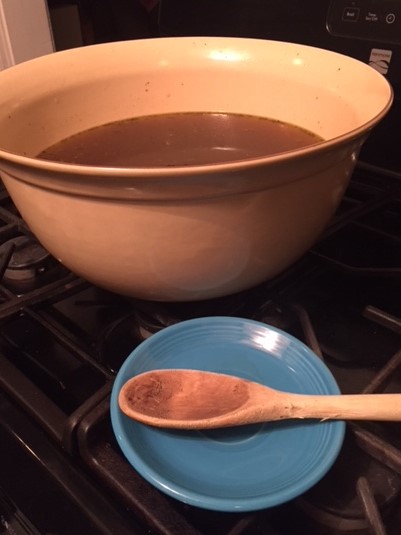

The veggies begin to caramelize; the shards of meat and the bones turn a beautiful brown. In an hour, I pull the pan from the oven and take it to the sink. I let the water run steadily until the pan is almost full, and then I stagger beneath its weight back to the stove. I set it down in the center of the stovetop and turn the middle burner on. I adjust seasonings and walk away, letting the alchemy begin.

******************

I can’t remember when I discovered that I didn’t have to buy broth to make soups and stews and gravies: I could use the homeliest, most neglected of orts and bits to make a wonderfully tasty stock. I pored through cookbooks, gathered recipes, sought advice. I tried and I erred, and I learned, finally, how to concoct a workable, tasty, effective broth.

The process pinged with me. I learned that many neglected items—veggies and bits of bony meat—scorned as leftovers or snacks, are welcome ingredients in a pot of broth. I learned too, that broth is not a place for the moldy or the spoiled, for things I wouldn’t serve to others or eat myself in the condition in which they now existed. Broth is a place to bring together misfits and healthy outcasts, but not a place to hide the flavors of unhealthy companions.

Broth is a living representation that sometimes, the resulting whole is bigger and better and more robust than the sum of its parts.

*********************

There are principles to making broth, I think as I settle back in my reading chair, letting the contents of that burgeoning pot warm and evolve and grow hot enough to simmer.

Like, “Don’t overlook anything, no matter how tiny or inconsequential.” Those little bits of green bean, that lonely clove of garlic—they don’t look like much, for sure. In fact, you might pass them right by, be inclined to discard them. But the broth would not be quite the same without their contribution—each player, no matter its size, adds something—zing or zest or depth or freshness.

Like, “Sometimes the things that seem obnoxious on their own are perfect and essential in combination.” I mean, onions, really—who wants to take a big bite of a raw onion? Who really likes to chop them, tears streaming, fingers getting pungent and tangy? An onion is not always a refined dinner pal. But we need onions in our broth; we need their pungent, earthy flavor. Overpowering when solo, onions rock in company.

Like, “It’s not going to happen in 15 minutes. Patience is a necessary ingredient.” I like to make the time for the roasting step, although it’s not absolutely essential. The caramelization, the roasty brown bits: these add deep rich color, and deep rich flavor, to the broth. And the long simmer is the learning process, where the flavors leave their own little spaces and merge, blending, extending, exploring, accepting. This cannot be rushed.

Like, “You must have some common denominators, but every batch of broth will be different in some way.” The bones, of course. The onion, a given. But I’m not always going to have the same stuff in my refrigerator. What goes in the pot will depend on season and feastings, appetites and energies. Every broth I make will be the same in some ways, and it will be different in others. The complexity makes each meal exciting.

Like, “Use the end result adventurously.” This broth, with chopped kale and orzo and tiny meatballs, could give me Italian wedding soup. It could also be the base for chicken tortilla soup, or build a roux for a pot pie. A few tablespoons of that tasty broth could flavor the next batch of homemade hash, and the rest could go into the white sauce for Alfredo pasta. Broth is a base, a beginning. And the end results can be excitingly varied.

****************

I was naïve; I thought the process was nothing more than putting leftovers in a pot, heating them with stock or water, and—voila, soup! Eventually I realized that it’s necessary to learn some simple techniques for maximizing flavor: how to make a good broth; how to begin a soup with a base of softened vegetables and herbs; and how to add either a single vegetable, for a pure and simple soup, or a combination of many vegetables (as well as pasta, meat, or fish) for a more complicated soup. The variation is endless.

—Alice Waters, The Art of Simple Food

******************

My son James loves to watch shows—Friends, How I Met Your Mother, The Big Bang Theory, even The West Wing—in which oddly fitting individuals come together, perhaps against great odds, to form a wonderfully cohesive whole. So the stunning blonde former cheerleader adds life and humor to a group of introverted physicists. The popular girl winds up, years later, with the geeky archaeology doc. Jocks and intellectuals, extroverts and shy guys, wealthy types and penny-pinching strugglers, all contribute to the wonderful whole they create. Quite often, the loss of a character, even a seemingly minor one, will change the show’s whole flavor.

Maybe some of those brothy principles apply to the congregation of people, too.

*****************

My cell phone bounces, jangling. It is my partner in crime, Becky, calling to sadly say she thinks we ought to cancel our first class meeting tonight. I check the weather. The temp is down to 34 degrees; there’s a brazen red banner across the weather website. All this rain is going to freeze. And then the snow will come.

I can hear it happening already. The rain drops that were gentle, then lashing, are pecking now, crashing against the bay window in metallic waves.

Becky and I divide up the list of participants, and we each make calls.

The news channel tells me local schools all dismissed early. Mark pops in from work at 2:55, sent home by his boss. I drag the reluctant dog outside to take care of business before ice glazes her pathways. She sticks her snout skyward, blinking,…wondering, I bet, what happened to our balmy morning weather.

And inside, the whole house is broth-perfumed. Jim is right: all other things being equal, the wonderful scent might sell a house.

****************

The light wanes and the temperature dives and we start the fire. The dog curls up, snoring, in one arm of the couch. We light lamps and pull out books and settle in. I think that a family has some things in common with a broth, disparate characters coming together, creating an unexpected, essential whole. The principles, above, apply.

The rain is morphing. First comes the sleet, and the world is glazed. In the neighborhood, the cars are pulled into the driveways; the lights are on. No traffic sullies the quiet.

And then, abruptly, the sleet becomes snow; the icy world turns white and silent. And inside, the fire snaps; a dog and a boyo snore, cozy in their perches. And on the stove, a deep, rich broth simmers.

When I was making my beef broth – with roasted bones and vegetables – I totally imagined this story!!! I’m so glad you wrote it – I felt every moment. Thank you for this – as we hunker in today – hubby recovering from knee replacement surgery – and both of us fighting a hacking cough and cold – likely picked up in the hospital – awh! Some broth would be divine right now.

Wish we were close enough for me to deliver!

I think we would be great neighbors….

I totally agree!

Ah…the smell of comfort…

You’re speaking my language here–learned it from my mother.

That’s a wonderful passing down!!!

So timely, Pam! I just made a huge pot of broth using all my oddments to add to two chicken carcasses. You’re right; any broth can benefit richly from all the odds and ends of vegetables and herbs. And the smell is just heavenly! We call it our ‘homemade cold cure” because even a sniffle goes away after we drink a cup of it.

Mmmmmm…We used the broth to make chicken tortilla soup yesterday: first time with a wonderful new recipe. And sinus troubles disappeared!

Y’all are going to teach me to make stock. I’ve been using the packaged Swanson beef vegetable, and chicken broth, and they’re all quite good, but since I have a good electric pressure cooker, I really don’t have an excuse for not making my own. (The only excuse I have is lack of time, since I cook mostly on the weekends, but that’s pretty lame.)

[John slinks guiltily away and almost doesn’t hit the “Post Comment” button. . .]

John! I read lately that one can make crockpot broth, although I have never tried it! What I love about it, though, is the ease…when you are home and at leisure, after that initial bustle, you just let it simmer….

No guilt allowed!!!

I can smell it now! A wonderful aroma!

We made a big batch of chicken tortilla soup with some of the broth…my first foray into that kind of soup. It was good!

That sounds so good Pam!

I’ve been makng broth my whole life and didn’t realize there was an oven carmelizing step. I just throw it all in a huge pot and boil. Your writing is so lovely.

Thanks, Cathy! I just discovered the oven step a few years back.

I’m definitely doing this next time.

Always interesting to read and learn from your cooking adventures Pam. Winter hasn’t quite arrived here yet, but often doesn’t – we haven’t seemed to have a full winter in the Midlands since 2010. The wind chill is biting though and weather alerts warning of strong winds and storm damage during next couple of days. Definitely time to knuckle down and prep veg for a pan of hearty stew to eat cold if the power goes down.

I brought 2 containers of organic broth. Just days before I read this blog. You may have inspired me to create my own. Love the idea of roasting first. How yummy.! Thank you for the inspiration. What is your class about? Sounds intriguing.

That roasting step just adds the best rich color, Kim–it’s not necessary, but it’s nice to do if time allows.

The Friday night class is called Family to Family,’ and it’s sponsored by NAMI–Becky and I co-facilitate a session once a year. It’s for families with a mentally ill member, and covers a wide range of things–from brain bio-chemistry (not that we’re experts in this area!) to how to communicate effectively with an ill loved one—and , maybe most importantly, self-care. I always get more than I give, of course– the valiant, compassionate, creative folks who take the course never fail to inspire.

Sounds wonderful! I bet you are good at it. On another note, when you speak of your son, Jim, in your blogs, I remember how much I enjoyed talking with students who were on the spectrum because they were so unabashedly who they were, so honest and forthcoming about what they were feeling.